Kitzbüheler Radmarathon 2024: Steep Mountains, cramps and big emotions

I rode the Kitzbüheler Radmarathon in September 2024 – and finished it. Here is my experience report.

Beware, this is going to be very long. I’ve been processing everything that’s happened this year, mainly for myself. If you like it, then even better. But take some time with you.

Here you find the german version of this text.

I’m at the last intermediate point. I have just over 200 kilometres and more than 3,000 metres of altitude behind me. My legs have been cramping since kilometre 170, first the insides of both thighs and then my calves. I had to let one group go, but another pulled me along to the intermediate point.

At this intermediate point, I have a choice: either I roll a few more flat kilometres to Kitzbühel and finish the somewhat easier basic version of the bike marathon – or I go up the Kitzbüheler Horn. Seven kilometres. Almost 1,000 metres in altitude. This means an average gradient of twelve percent and at least 20 percent at maximum. So if I ride the Horn and give up, there is no finish for me.

I stretch my legs, stretch my whole body, chase down one iso drink after another at the intermediate point and eat bananas. Despite my cramps, I don’t think twice: the horn or nothing. If necessary, I push the bike up this mountain by feet.

In a film, that would be the part where the movie stops and I say from the background: ‘Yup, that’s me. You’re probably wondering how I ended up in this situation.’

Kitzbüheler Radmarathon 2024: Why?

So let’s start at the beginning. I’m Justin, I’ve been riding a road bike since August 2022. Back then, I was fulfilling a childhood dream. I particularly enjoyed following the Tour de France as a child and followed it emotionally, imitating big stages on my childhood bike in my home village.

At some point, I lost touch with cycling due to the doping scandals and my focus on football, before I found it again in the 2010s, first as a spectator and then in 2022 with my own road bike. I’m not going to go into the whole story of how I managed to get so fit between August 2022 and September 2024 that I felt confident enough to take on a bike marathon.

But I realised relatively quickly in the winter of 2023/24 that I wanted to do one. I actually had my sights set on the Ötztaler. So I applied together with my training partner in January – and we were both rejected. My training partner then suggested the Kitzbüheler a few weeks later. I looked at the profile and said: Perfect. How naive of me.

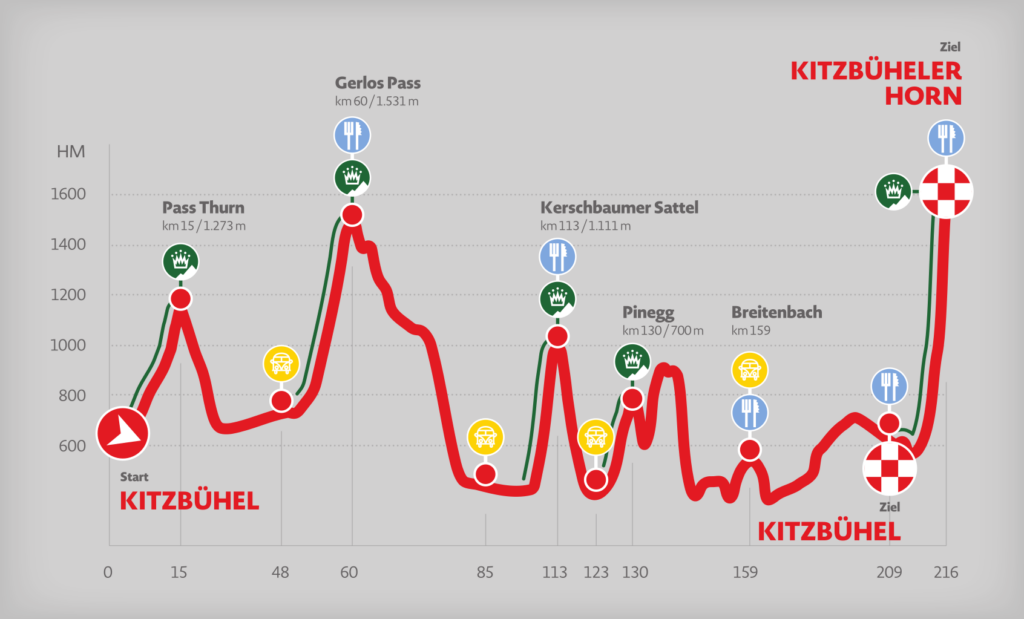

Kitzbüheler Radmarathon: The profile

The claim ‘Really steep’ is no coincidence in Kitzbühel. There are a total of five mountains worth mentioning. The Pass Thurn is a good warm-up programme with an average gradient of just three percent. It is long and almost flat for a long time. Only at the end does it get a little steeper, but still moderate with a maximum of seven or eight percent or so.

The Gerlos Pass is more difficult. The first half is in parts very steep, with gradients of up to twelve percent, and it only flattens out a little at the top. Then there’s a intermediate point at the top, a long descent and a fast flat section to the first hard one: the Kerschbaumer Sattel. Five kilometres, 10.7 percent on average and hardly ever less than nine or ten percent.

Almost immediately after the descent, there are further climbs around Brandenberg and Pinegg, most of which are moderate, but with peaks of over ten percent. Once you have mastered this, there is actually a fairly simple-looking but long stretch to Kitzbühel. At least you think so. More on this later.

The Horn is the final boss. Almost 13 percent on average over just seven kilometres. Hallelujah, what did I sign up for?

The preparation

Especially as the biggest joke is that I’ve only been to the Alps once in my life. And I’ve only done one bike tour there with a little over 2,000 metres of elevation gain in just over 100 kilometres. Apart from that, I once rode up the Brocken in the Harz.

I come from Brandenburg. To climb 4,000 metres in altitude here, I would either have to pedal up and down bridges or ride at least 1,000 kilometres. There are gradients of over ten percent here and there if someone has been bored building a road or path on a very little bump, but none of that is suitable for training.

So how do you prepare as a flatlander?

The training

Firstly, it is important to note that I am not a scientist and have only read up on all of this, so please do not take this as a recommendation for action, but above all as a report on what has worked (or not worked) for me.

It is clear that various components are required to complete such a bike marathon. Which ones are needed and to what extent depends on what goal you set yourself. Some just want to get through, I wanted to get through with the best possible time. Minimum goal: under nine hours.

If you want to finish somehow, you will ride a lot in the comfort zone. In other words, in the so-called ‘Zone 2’. This is the area in which the body only feels a moderate intensity. It is often said that you are in this zone when you can still hold a relaxed conversation while jogging or cycling. You can also call it the endurance zone. At this pace, once you reach a certain level of fitness, it no longer matters whether you spend four, five, six or ten hours on the bike.

However, a large endurance base is also relevant for those who want to finish with the best possible time. But for me there are other factors too. Over several hours, you want to avoid getting into the red zone too often. In other words, the area that is above the threshold power (the power that you can pedal for about an hour) – also known as the anaerobic zone.

In the anaerobic zone, more lactate is formed and the body no longer gets enough oxygen to produce energy. In simple terms, this means that at some point you burst and nothing works any more.

How my training was structured

Roughly speaking, two aspects were very important to me in my preparation: a large endurance base and shifting the anaerobic threshold in order to pedal as high wattage as possible without getting into the red zone.

Between January and April, I was still going quite unstructured. Lots of base units, i.e. long rides in zone 2, but also lots of races on Zwift. Things became more concrete from May onwards. That’s when I started to prepare more specifically.

In a first long block over around six weeks, my focus was on Zone 2 training. At least four sessions a week, one very long ride of between three and six hours, two to three shorter Zone 2 rides (sometimes with short tempo or threshold intervals in the higher aerobic zone) of between two and three hours and a one-hour, harder workout with intervals in the anaerobic zone. At least one rest day per week. At least 80 percent in zones 1 and 2, 20 percent in more intensive zones.

In all blocks, I spent between 8 and 15 hours a week on the bike. Depending on how much time I had myself. I wasn’t always able to stick to my plan, but almost always.

My second larger block, also six weeks long, had a similar structure. However, I now increased the proportion of more intensive zones so that my training became more ‘polarised’. At least two hard days per week with anaerobic intervals, plus a zone 2 unit with longer tempo intervals (zone 3). I won’t explain the zone model in detail here, but you can find information with google very fast.

In both training blocks, I always tried to increase the intensity for three weeks and then integrate a week that was slightly less intense. This was followed by two progressively more intensive weeks before moving on to the next training block.

The third block, i.e. the six weeks before the competition, was about simulating specific performances that I would need in Kitzbühel. For example, a five-hour ride with two 40-minute intervals in tempo zone – the range in which I will be in for the most parts of the climbs.

Ideally with a low cadence to simulate what it will be like on the mountain. This is rather difficult on the flats in Brandenburg. That’s why I did some of these sessions on the turbo trainer and on Zwift to get used to low cadence at higher watts. A workout that I also found very helpful: Three to four hours, three to four 20-minute Zone 3 intervals, into each of which you integrate four to five one-minute power increases into the anaerobic zone to get the body used to lactate building. It was tough but you get a lot of confidence from it.

In the last training block, I then progressively trained for four and a half weeks before going into tapering for one and a half weeks, i.e. the regeneration and activation phase before the competition.

In addition to training on the bike, I did yoga at least three times a week (sometimes even daily), which significantly improved my flexibility. It’s a game changer, especially on long rides, and you can stay calmer on the bike even at high intensities because your body doesn’t get stiff as quickly.

The bike

At this point, a brief comment on my equipment: I rode the Cube Agree C:62 Race. Gear ratio 11-34 at the rear and 50-34 at the front. I got on very well with it, no matter how steep the terrain. The wheelset is from Leeze, more for flat areas, but so what?

The pace plan

About a month before the race, I started to think more concretely about how I would approach the race. My plan was rough: zone 3 on the climbs, regenerate downhill, as much zone 1 and 2 as possible on the flat and lots of draft.

Then I got more specific. My FTP (i.e. the approximate power I can maintain for an hour) is between 330 and 350 watts at 80 kilos – just over four watts per kilo. Various studies and experience reports show that you can manage climbing in a bike marathon very well at around 80 percent of your FTP. In Kitzbühel, you never reach an altitude where you have to reckon with a severe drop in performance. The Ötztaler is different. My plan looked like this:

- Pass Thurn: find a good group, around 270 watts on average

- Gerlos Pass: tackle the steeper half with around 270-300 watts, then 250-270 watts to the top in the flatter section

- Kerschbaumer Sattel: as constant as possible at around 270-280 watts

- Pinegg/Brandenberg: around 260 watts

- Horn: everything left in the tank. Ideally closer to 250 or 260 watts or even more if things are going perfectly. But start defensively and possibly increase in the second half.

The nutrition

If you want to do a lot of endurance sport, you have to remember to supply your body with electrolytes and, above all, carbohydrates during longer sessions and especially at events like this. Professionals used to consume around 60g of carbohydrates per hour. Modern sports science research has now come so far that professionals consume up to 120g per hour – and that makes an extremely performance-enhancing difference.

But I’m not a professional. Even if I ride at the limit, I won’t get into areas that require even the smallest percentage of nutritional optimisation. Especially as I won’t have a car from which everything is happily handed to me. So I had to find a compromise between the space I have on my bike and in my jersey and a good nutrition. 60-80g of carbohydrates per hour seemed possible and sufficient.

I decided on the following – stored in a slightly larger saddle bag, my frame box and my jersey (see picture of the bike below):

- Ten gels with 40g carbohydrates

- Two caffeine gels with around 20g carbs

- Two bottles with 0.75 litres of water each – one filled with around 80g maltodextrin and a typical electrolyte mixture

- Two emergency bars (I don’t like solid food while riding too much, but sometimes I need it to feel good when just fluids are not enough)

- An emergency pack with electrolytes

- Three small zip bags with 80g of maltodextrin and electrolyte mix to refill the bottle

The aim was to stop at every intermediate point (see profile above), refill the bottles and eat something if necessary. All with as little loss of time as possible.

For breakfast, I had a huge bowl of porridge, two beetroot shots and a litre of water, which I was able to (partially) bring away to the toilet in the start zone before I started.

Of course, I took a closer look at the intermediate points based on previous years and the information on the website. Unfortunately, cakes and other nice things were not vegan. For me, there was actually only fruit, dry bread and iso drinks. But that was enough for my plans. After all, I hadn’t travelled here for a feast.

By the way: what hardly anyone tells you when you read yourself into nutrition with sugar water, gels etc., but which is of course logical, is the strain on your teeth. I was one of those who gave it less thought. But of course all that stuff attacks your teeth. So you have to develop a routine to combat this. For example, rinsing with water after every sip from the sugar bottle and after every gel, and not keeping the stuff in your mouth for too long.

The race

Now to the race day itself. We had perfect weather conditions. A first for the fourth edition of the bike marathon. It stayed dry until 3 or 4 pm, then it drizzled very little on the Horn, but even that wasn’t real rain.

I took a gamble and left my rain jacket at home. More storage space in the jersey. I wore arm warmers and a wind waistcoat at the start in addition to the jersey and bib. The first two or three hours were still quite chilly, but it went very well.

Really fast start

I warmed up quickly at the beginning anyway. Finding a group wasn’t that easy. Again and again I had to get almost to the threshold area to find a well-functioning group. I only found a good rhythm in the steeper section of the Pass Thurn. But I think some of the riders completely overdid it here.

Pass Thurn

The climb itself was predictably easy to ride and the ascent from Kitzbühel is not particularly beautiful. But it was the expected good warm-up ride. And the descent that followed was wonderful. After one or two hairpin bends, we were rewarded with the still low sun and an outstanding view of the valley.

Some of us really let it rip downhill, I remained cautious and ‘only’ reached 65 km/h at the top. Quite fast for an inexperienced downhill rider. We then headed through the valley. At the start, we were a very small group of just four or five people.

However, we had eye contact with a larger group and so we took turns in the lead to catch up. However, I never went higher than 300 watts. When we reached the group, things got better. Lots of draft.

Gerlos Pass

It took a few kilometres until we finally arrived at the Gerlos Pass. And that one surprised me a little. I knew that the start was steep, but it felt more difficult than I had expected. Nevertheless, I kept my target pace quite well here and made it to the first intermediate point without any major difficulties.

It was really busy here because the field wasn’t very spread out yet. So the staff had a lot to do. I put my bike on the grass, took the first malto bag out of my pocket, poured it into the bottle, topped them both up with water, which was surprisingly quick, and got back on my bike. Not too much of a break. Off into the descent.

This descend was also very nice. I was alone at the start, but a large group caught up with me and I joined them at the back. Riding behind others was easier. Especially in the second part of the descent with lots of hairpin bends. There we overtook three cars as a group, but some of us couldn’t get past in the now winding section. This led to a rather … modest situation.

Long flat part

In the flat section that followed, there were only three of us and then even two. The group in front of us rode further and further away and we wasted some energy trying to catch up again. No chance.

My partner dropped off while I was leading, which I only realised after two minutes. I also pulled out and realised that there was no point. Fortunately, a new group soon arrived and we rode with them up to the Kerschbaumer Sattel. The ride down into the valley was equally beautiful in terms of the surroundings.

The roads and the people who cheered us on or pointed us in the right direction were also outstanding. Very good organisation – all along the route.

Kerschbaumer Sattel

The first really hard climb was waiting for us at Kerschbaumer. But I have to say that the mountain was really fun. There were a few people at the edge cheering us on and although it was steep, it was much easier to find a rhythm than on the previous climbs. I liked that.

The next intermediate station was waiting at the top. Here, too, I minimised my time. Same procedure as the first one.

Pinegg/Brandenberg

During and after the descent, a group formed around ultra-cycling legend Christoph Strasser, who accompanied participant Anna Moser as mental support. The group was very pleasant and also rode in zones, which brought me some recovery. However, the climbs that followed surprised me a little. They were longer than I had expected and sometimes steeper than I had anticipated.

Overall, I was glad that the group took a more moderate approach and so I mostly stayed at around 240, 250, sometimes 260 watts. More would not have been worth it. Why leave the group? The descent from Brandenberg to Kramsach was simply marvellous. Unbelievable. Great tarmac, incredible views. I sometimes reached speeds of just under 80 km/h without realising it. I will never forget this descent.

The turning point

It was still a bit hilly with some ups and downs to the next intermediate point, which was waiting for us at around 155 kilometres. I was doing really well until then. I got another refill for the bottles and continued on. Unfortunately, Strasser was quicker and I didn’t see him again for a while.

There was another group shortly afterwards, but they rode quite fast. From 170 km onwards, I could already feel the beginnings of cramps in my inner thighs. I tried to stretch my legs at every chance I got while riding and to increase my fluid intake. It helped for a short time, but the pain came back stronger. Especially as two uncategorised ramps with up to 15 percent demanded a lot.

My calves cramped even more at 190 kilometres. I let my group go on one of the short climbs and joined a slightly slower group later on. I soon let them go too, but only just before the intermediate point. And there I was. Faced with the decision of how best to conquer the Horn.

The fight against my body

I ate everything I could find at the intermediate point. And then I rolled towards the horn after my longest break yet. My time was outstanding. Something around seven hours and a few minutes. Without cramps, I would probably have been aiming for a time of around eight hours and 10 or 20 minutes.

But I had to change my mental approach: Arrive somehow. I rode into the left-hand bend and there were people at the bottom of the hill applauding all the riders who came that way. It was such a nice feeling. ‘Respect,’ shouted one. I replied: ‘Maybe I’ll see you soon, I’m cramping all over. But if necessary, I’ll push the bike up this fucking hill.’ He laughed. I didn’t.

At first it was still a roll-in. Then I saw this:

From then on, it only got steeper. It was crazy. With every turn of the pedals, I was afraid that something in my legs would close up completely. I had to be so careful not to overdo now. I tried to stay in the range between 200 and 240 watts. Which on this climb meant a cadence of 30 to 50.

I could see the ascent and my progress on my bike computer. The first three kilometres went okay, then everything dragged on indefinitely. I zigzagged a lot to reduce the gradient and take it easy on my legs. Some people were already pushing their bikes by feet. ‘How much further,’ asked one. The answer wasn’t really motivating.

There was simply no end to it. I stopped the route guidance on my bike computer because the progress indicator was getting on my nerves. After a good four kilometres, I stopped for the first time because I had to. Stretching my legs, massaging my calves, somehow delaying the fact that my body no longer wanted to. Back on the bike.

After five kilometres I had to get off the bike again. After all: only about two kilometres to go. Now I could make it on feet if necessary. I got back on my bike. Then the most brutal part came up. Up to 20 per cent in a small wooded area. You could hardly make any progress. From right to left and back again. For me, it was all about my mind, all about surviving. Somehow I had to keep turning my legs despite the incredible pain.

We passed through a first ‘gate’. I thought it might be the 1 kilometre mark. As we came out of the forest, I looked up. Another green gate and even further up, the finish. It looked so far away. But I could see it.

I gave it everything I had to get there and then the moment arrived. The finish line. I raised my fist with the last of my energy, clicked off the pedals, sat on the top tube, buried my head on the handlebars and started to cry. I was so proud, so happy, so overwhelmed by everything I had experienced that day. So fulfilled and so empty at the same time. I had really got it.

And in a time of eight hours and 46 minutes. Minimum goal achieved. Despite the cramps and the unexpected problems. I still can’t really realise today how I managed it.

Analysis: What went wrong in the end?

In hindsight, I still had to analyse for myself why I ended up with cramps. If only to do better next time.

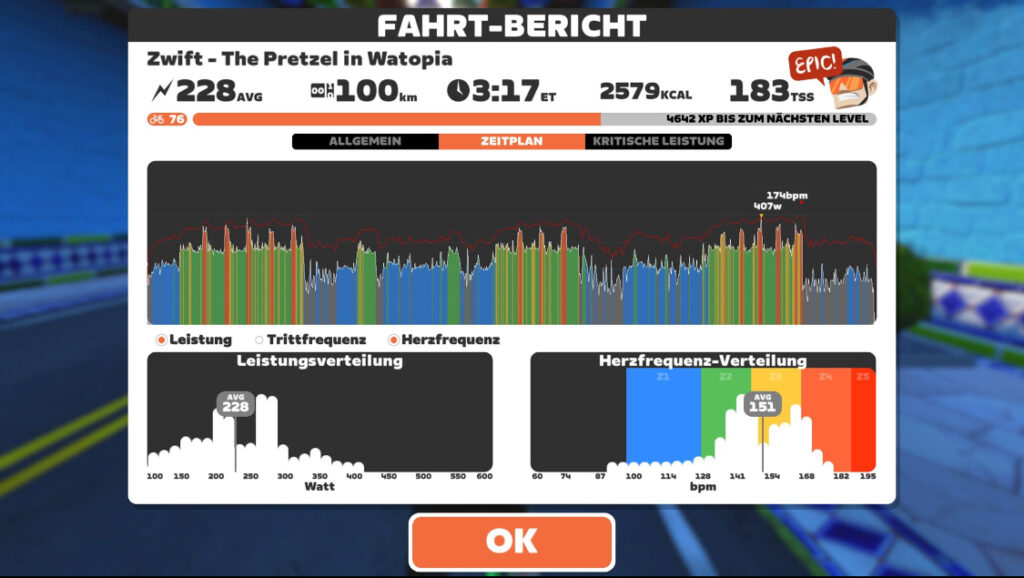

If I look at my pure performance data, I’m actually quite satisfied. I spent around three hours in zones 3 and 4. Most of it was between the 250 and 300 watts I was aiming for. Here are my wattage values for the climbs:

- Pass Thurn: 269 watts

- Gerlos Pass: The steep section with 275 watts, then significantly less towards 230/240 watts

- Kerschbaumer Sattel: 270 watts

- Pinegg/Brandenberg: 210 watts (whereby short intermediate descents and flatter sections pull the average down) – on the climbs it was more like 240 watts on average

- Horn: 197 watts (with the two short breaks)

Apart from the Horn, I’m totally satisfied with the results and everything went according to plan, except for the mountains. However, there are two sections that, looking back, didn’t go perfectly.

This is the section after the descent from Pass Thurn to the Gerlos Pass. I pushed an average of 225 watts. But as you can see, there are a lot of yellow areas in the second row. This is my tempo zone. The graph shows the 30-second average. I was travelling too long in a zone where I couldn’t recover. Maybe I should have waited for a group behind me instead of chasing the one in front.

This also applies to the section after the descent from the Gerlos Pass. I could have, and probably should have, saved a lot more energy, especially on the flat sections. I was too impatient here and too worried about not being able to maintain my good time. I never rode dramatically too hard on the flat sections, but perhaps a tad too hard, which was decisive in the end. But you just feel good and then you take the risk.

Nutrition

But there may also have been a few mistakes in my nutrition. I still had four 40g gels and one caffeine gel left at the end. In other words, I only consumed six 40g gels and one caffeine gel in just under nine hours. Less than the planned one gel per hour. I actually always emptied my bottles well before heading to the next intermediate stop.

However, I didn’t eat anything there. No bananas either. Perhaps it was too little overall, which could have favoured the cramps.

Kitzbüheler Radmarathon: What would I do different next time?

This also leads to the question of whether I would do anything differently if I were to do it again. As far as preparation is concerned: No. At most an additional “vacation” in the mountains, if time permits. Seriously, Zwift can prepare you very well for what you need in the mountains. My performance shows that very well.

But: Riding uphill is different to riding on a turbo trainer. The incline puts a different strain on the body. Afterwards, I had pain in places I didn’t know existed. So at least some training in the mountains would be desirable for someone like me, who is happy about every bridge in Brandenburg.

But the training itself was great. I felt fit to the point. So I seem to have done a lot of things right. Next time, I would make sure that I eat more regularly. So not two big gulps from the bottle and then not at all for 40 minutes, but really a little every few minutes. And really use the gels I have.

And I would eat a lot more bananas at the intermediate points next time. The few seconds are a must. Maybe then it will stay cramp-free. But hey! This was my first bike marathon. And it went very, very well. I got to know my limits and overcame them. I proved my mental and physical strength – and I had a perfect mix of fun and pain.

Danke!

Once again, I would like to thank everyone who has helped me along the way.

- My girlfriend Nina, who endured all the preparation process and always supported me

- My training partner Roland, who got everything rolling in the first place and made it all possible. Chapeau to him for also finishing the bike marathon – despite several tough setbacks this year

- Team Vegan – a wonderful community that has supported me on my journey for two years. I’ve made friends there and received valuable tips. Thank you!

- Bike Academy Berlin: An excellent bike fitting that enabled me to achieve the final percentages

- Thanks also to everyone who has given me positive encouragement for weeks and who cheered and suffered with me when I finally made it

- And thanks to the organizers. A really great event!

0 Kommentare